Compost additives

Compost starters usually contain organic nitrogen, bacteria and fungi. In moist compost they become active and are involved in the composting process. However, they can only develop their effect when the right conditions prevail in the compost, i.e. the compost consists of a good mixture of organic materials, is loosely composted and contains sufficient oxygen. If this is the case, the rotting process will proceed without the help of compost starters.

Please Note

A well established compost does not need any compost additives or finished compost accelerators.

If you want to get composting going quickly, it is a good idea to „inoculate“ the compost, i.e. add a few shovels of stem compost (older compost) to the new compost.

Some additives can help you regulate the compost, for example if it is too acidic, too wet or too low in nitrogen.

If your compost contains a lot of lawn clippings, coniferous wood and needles, adding lime (e.g. algal lime) can be helpful (up to 2 kg/m3) to bind the acid released during the composting of these materials.

If your compost is too wet, you can improve it by adding primary rock flour (2 to 3 kg/m3) to alleviate the problem.

If your compost is mostly composed of low-nitrogen materials such as wood chips or straw, you can balance it out by adding nitrogen-rich materials such as manure or fresh grass cuttings.

Composting methods

Hot composting

If you have the option of making compost in one go, as described above, it has the advantage that the individual stages of rotting take place simultaneously throughout the compost material. The compost can heat up to temperatures between 60 and 70 °C. A large compost can hold the heat for several weeks. This can kill pathogens, germs and weed seeds.

Cold composting

In many small, private gardens, too little organic material accumulates at once, so the compost is built up slowly, layer by layer. The rotting stages in the layers therefore also take place one after the other. This means that the layers can have different stages. In each case, the most heat is generated in the uppermost layer; in comparison to the hot compost, temperatures of up to 40 °C are usually only generated here due to the rather small compost volume and the associated lower activity of the microorganisms. Since the layer is not insulated, it cannot hold the heat for long and cools down again quickly. The compost therefore takes much longer to mature.

Please Note

Due to the low temperatures, cold rotting cannot ensure that pathogens and weed seeds are completely killed.

Composting process

The composting process takes place in four stages: mesophilic, thermophilic, cooling, and curing. The stages cannot always be precisely delineated. For the composting process to proceed as described below, a minimum compost size of about 1 m3 (1,000 litres) is required. The compost must also have been built up all at once.

Stage 1: The Mesophilic Phase

The first stage is fast (within a few weeks). Mesophilic (medium temperatureloving) microorganisms break down easily soluble compounds (proteins, sugars and fats). Ideal conditions in the compost contribute to the rapid multiplication of the organisms. The temperature in the compost rises to over 50 °C. The metabolic activity of the microorganisms generates heat. Since the rotting process can only conduct the heat poorly, the heat accumulates in the compost. Hygienisation begins. In addition to heat, thermophilic (high temperature-loving) microorganisms and their metabolic products are involved in hygienisation. Weed seeds, pests and disease germs are thus killed. Residues of pesticides and antibiotics are also decomposed. If the compost is composed of a sufficient amount (at least 1,000 litres) of well-mixed organic material, the temperatures rise up to 70 °C. Afterwards, the temperatures drop again.

The organic material is now broken down into its basic building blocks. The decomposing organisms die and serve as food for other organisms. The rot has turned from green to brown/black-brown.

Stage 2: The Thermophilic Phase

Now, in addition to mesophilic bacteria, fungi that specialise in breaking down substances that are difficult to utilise, such as cellulose and lignins, are active in the compost. The temperature drops again to 30 to 45 °C.

Stage 3: The Cooling Phase

Humic substances are formed. Fungal growth decreases. Small soil animals such as mites, springtails, beetles, woodlice, dungworms and compost worms migrate into the compost and ensure that mineral and organic parts are mixed together. Stable crumbs are formed (clay-humus complex).

Stage 4: The Curing Phase

Humus formation and mineralisation are completed. The compost worms leave the compost. Mature compost is formed. The humic substances give it a dark brown colour. The material is now loose and crumbly, indicating the completion of composting. The original material is no longer recognisable as such, except for pieces of wood and woody stems. (You can sieve out the wood pieces and add them to the next compost).

Hygienisation and pasteurisation

While plant material can be composted more or less safely, faeces can contain germs and pathogens that are harmful to human health.

Here, the focus is on your own responsible action. The legislator assumes that you have an interest in spreading a low-pollutant and hygienically safe, high-quality compost on your beds and that you therefore choose the organic source materials for your compost carefully and compost them properly and, if necessary, sanitise them.

Composting is properly sanitised when the following conditions are met:

- The water content is at least 40% over the entire period.

- The pH value is around 7 over the entire period.

- In the compost, temperatures of at least 55 °C prevail continuously for 2 weeks, or temperatures of 60 °C continuously for 6 days or temperatures of 65 °C for 3 days.

However, the temperatures required for hygienisation only occur during hot composting. For this, as already described, the compost must have a certain volume and be placed in one piece. If the compost is placed layer by layer, the compost will not develop the required temperatures.

In the case of self-composting by hot composting, there is also the following difficulty. While you can control the temperature and pH with a compost thermometer and litmus paper, you will have difficulties to find out the exact water content of the compost. Therefore, when composting on your own, it is difficult to check whether the prescribed conditions for proper hygienisation have actually been met.

The WHO recommendation

The WHO (World Health Organization) therefore recommends composting for a period of two years. Since the compost poses a health risk during this period, filling and handling of the compost must be carried out under hygienic aspects, according to the WHO.

Monitoring composting

In order for composting to proceed quickly and without problems, favourable conditions must prevail in the compost. Therefore, you should monitor the temperature, moisture and acidity during the composting process.

Temperature

Particularly in hot composting, monitoring the compost temperature is indispensable. With a compost thermometer (see also useful tools) you can measure the temperature in the compost directly and lower or raise the temperature if necessary. Adding fresh grass cuttings can increase the temperature. By watering the compost you can ensure that the temperature in the compost drops.

Moisture

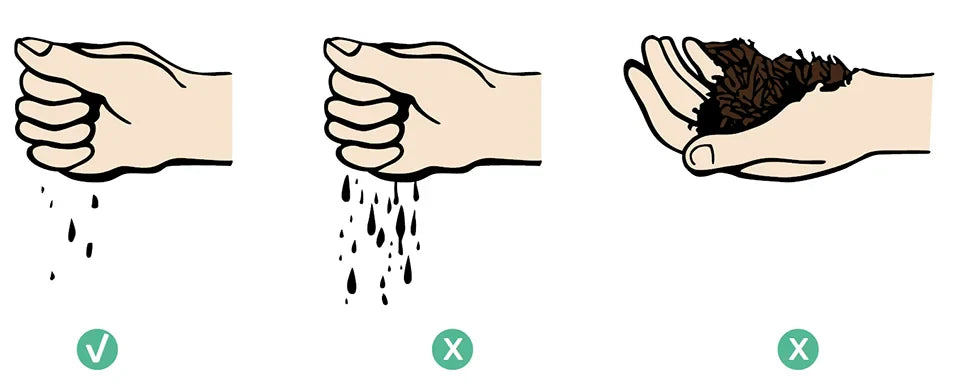

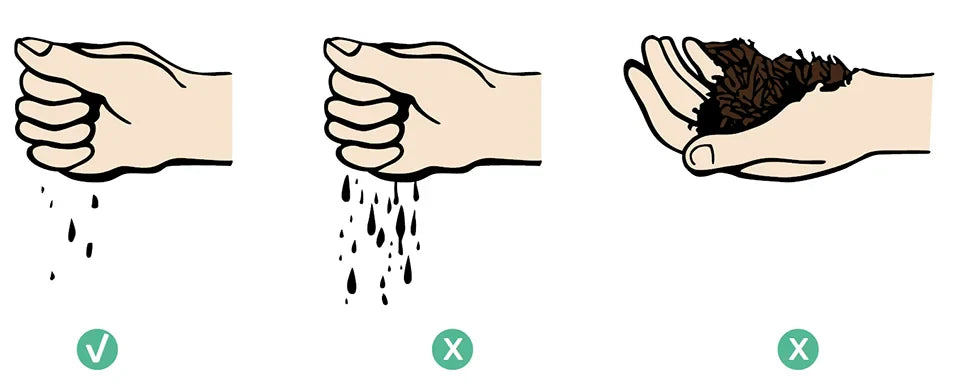

During the decomposition phase and in summer there is a risk that the compost will dry out. In autumn and winter, when it rains a lot, you should make sure that it does not get too wet. The compost should be moist, but never wet. With the fist test you can quickly and easily determine the moisture content of the compost. Correct moisture: When you squeeze the rotting material in your fist, only a few drops come out. If you open your hand, the material will hold together. Too wet: When you squeeze the rotting material in your fist, water flows out of the material. Too dry: No water comes out when you squeeze the rotting material in your fist. If you open your hand, the material falls apart, like sand.

Oxygen

If the rotting material smells earthy and like fresh forest soil, there is sufficient oxygen in the compost. If the material smells rotten or sour, there is a lack of oxygen in the compost.

The compost loses volume (approx. 50 %) in the composting process and sinks. Accordingly, there are now fewer cavities in the compost.

Water can no longer evaporate as well and oxygen can no longer be supplied to the compost well. There is a danger that some areas in the compost will remain without oxygen and anaerobic processes will take place here. This must be avoided, as rotting could occur.

Unlike rotting, which releases carbon dioxide, water, humic substances and trace elements, putrefaction produces gases that are harmful to the climate, such as methane and nitrous oxide. Rotten compost is not only useless because it does not form humus, but it is also harmful to the climate.

Possible problems and measures

Below we have compiled a table with possible problems that could occur and the corresponding measures.

- Compost is too dry.

Transfer and water compost and/or add fresh lawn cuttings. - Compost is too wet, smells putrid.

Turn compost and add dry material such as straw and/or wood chippings, if necessary also add some primary rock flour. - Compost is too hot.

Turn compost and mix with soil. - Compost does not become hot.

Add fresh lawn clippings - Composting proceeds too slowly.

Turn compost, add nitrogen-rich materials such as kitchen waste and manure, water if necessary. - Compost is full of fruit flies.

Cover fresh and rooted material with soil, loosen compost material, add primary rock flour if necessary.

Turning the compost

In the course of the composting process, the compost loses volume, it collapses. Hollow spaces that held the oxygen in the compost disappear. Oxygen deficiency occurs. For this reason you should turn the compost as often as possible, i.e. loosen it up with a digging fork and mix it. In this way you ensure that the compost material is well aerated again and at the same time you stimulate the activity of the micro-organisms. The temperature in the compost increases again and composting is accelerated.

During turning, you can check the compost for moisture. Work the layers around the edges into the pile and water dry layers if necessary.

The compost should only be turned for the first time after the decomposition phase, when the temperature has dropped to approx. 45 °C again. After that you can turn the compost several times. Do not turn the compost in winter.

Please Note

The more often compost is turned, the faster it can mature.

Use, spreading and storage of compost

Use

The rotting time has an influence on the use of the compost. Depending on the rotting progress (maturity), a distinction is made between fresh compost and mature compost.

Fresh compost

Fresh compost is approx. 3 to 4 months old and has not yet been completely transformed into compost humus. Compared to mature compost, it has a coarser structure and is colonised by soil organisms. In autumn you can use fresh compost to mulch strawberries, berry bushes and hedges. It should not be used for sowing, as it inhibits seed germination and damages the roots of young plants. Fresh compost is not suitable for repotting houseplants or for planting balcony flowers.

Mature compost

After about 4 to 8 months, the compost is ripe. The dark brown, almost black mature compost has a loose, crumbly structure and smells like fresh forest soil. It is versatile and can be spread on both vegetable and flower beds. Mixed with soil (70 % garden soil and 30 % compost) you can use it for planting balcony flowers and repotting houseplants. To support the growth and health of the plants, it is advisable to always add a few shovels of compost when sowing.

Mature compost not only helps to rebuild depleted soils with nutrients, it also improves the structure of so-called „problem soils“ such as sandy, loamy or clayey soils. Sandy soils can store water better, clay soils get a looser structure and clay soils can be worked more easily.

Spreading

Compost should only be worked into the soil superficially, but not dug under.

It is recommended not to apply more than 3 litres of compost per m2 to the soils per year (the optimal amount can vary between 1 and 3 litres per m2 depending on the nutrient requirements of the respective crops). If the soils are depleted or if a garden or bed is newly established, then 10 kg of compost per m2, i.e. a layer of 1 to 2 cm, can be applied once.

Please Note

Using compost as fertiliser is quite sufficient.

Storage

Mature compost should not be stored for more than one year, as nutrients are lost over time.

Cress test

With the cress test you can determine the degree of maturity of the compost. Mix one part garden soil with one part compost and put the mixture in a small bowl. Now scatter cress seeds evenly and place the bowl in a sunny spot, e.g. on the windowsill. Use a flower sprayer to keep the soil moist. The cress seeds should germinate after a few days.

If the cress germinates irregularly and the leaves are yellow, it is a sign that your compost is not yet ripe. If, on the other hand, you can observe regular germination and the leaves are strong and green, you can assume that your compost is ripe.

Useful tools

Digging fork

You can use the digging fork for turning the compost. It is also suitable for working the finished compost into the soil.

Pitchfork and shovel

With the help of a pitchfork or shovel, manure, mulch and compost can be easily transported into a wheelbarrow.

Spade

You can use a spade to shred robust compost material, among other things.

Garden and hedge shears or shredder

Prunings from trees, hedges and shrubs can be shredded with garden shears or hedge trimmers to prepare the compost material. If you have a lot of material, you should consider buying a shredder.

Watering can

A watering can is a good way to water the compost.

Wheelbarrow

The wheelbarrow is not only suitable for transporting compost from A to B. You can also use it to transport many other garden materials such as soil, wood, leaves or garden tools.

Compost sieve

With a compost sieve you can easily sieve the finished compost. Pieces of wood and stalks that have not yet rotted can be easily sorted out.

Compost thermometer

A compost thermometer is important so that you can measure the temperature in the compost during composting. We recommend a stainless steel compost thermometer with a measuring probe at least 50 cm long. The thermometer should be able to display temperatures in the range of at least 0 °C to 80 °C.

The Bokashi Bucket – an alternative to compost

Bokashi originated in Japan. It offers a good alternative to compost. The organic material is collected in an airtight Bokashi bucket and sprayed with an EM solution. The EM solution contains Effective Microorganisms (lactic acid bacteria, yeast, photosynthesis bacteria) which ensure that the organic material in the bucket ferments. Within 2 weeks a liquid is produced that can be used as a liquid fertiliser. The fermented organic material is very acidic and first has to be„earthified“, i.e. mixed with soil (2/3 fermented material and 1/3 topsoil), before it can be used as fertiliser. The process of „digestion“ takes about 12 weeks.

In bokashi you can collect all organic kitchen waste. In addition to fruit and vegetable scraps, citrus peelings, coffee grounds, you can also add cooked food scraps such as pasta, rice, bread, small amounts of meat scraps, cold cuts and milk products to the bokashi bucket. Note that it takes a long time for the animal material to ferment. It is therefore recommended that cooked food scraps and organic waste of animal origin should rather be disposed of in the organic waste bin. There is also a risk that the fermented animal materials will attract vermin during the „digestion“ process.

If you don‘t want to compost your garden, a bokashi bucket is a good alternative to make your own environmentally friendly fertiliser.